Hedge Fund Risk, Return, and Diversification: What Investors Need to Know

Hedge funds have long been positioned as elite investment vehicles, promising access to sophisticated strategies and superior returns. But behind the headlines and high fees lies a more nuanced picture—one that demands a deeper understanding of where returns really come from, what risks are being taken, and how hedge funds can fit into a broader portfolio.

This article explores the risk-return profile of hedge funds, the hidden biases in their reported performance, and the role they can play in portfolio diversification.

The Anatomy of Hedge Fund Returns

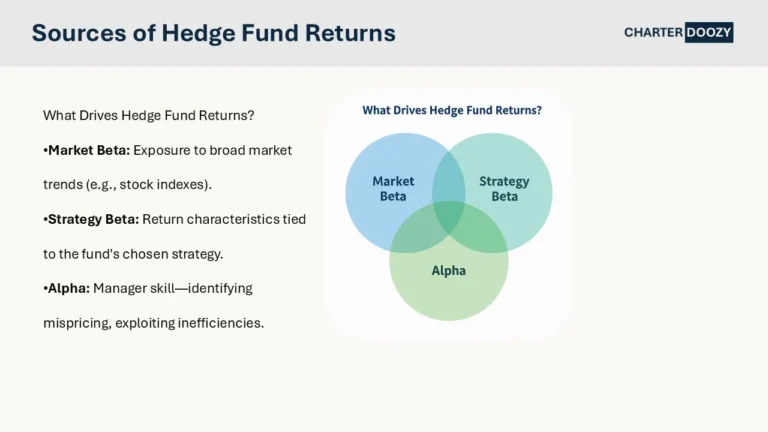

At the heart of hedge fund investing is the pursuit of alpha—returns generated through manager skill rather than exposure to general market movements. While traditional funds largely deliver beta—returns tied to broad market indexes—hedge funds aim to find inefficiencies, exploit mispricings, and capture idiosyncratic opportunities that the broader market might miss.

In reality, hedge fund returns are typically made up of three components. The first is market beta, which reflects the portion of performance attributable to overall market trends. The second is strategy beta, which captures the return characteristics of the hedge fund’s particular strategy—whether that’s long/short equity, event-driven arbitrage, or global macro positioning. Finally, there is true alpha, which represents the manager’s unique ability to generate excess returns through skill, insight, or execution edge.

In theory, alpha is what investors are paying for. In practice, separating alpha from beta is no easy task.

The Fee Structure and Its Impact

One of the defining features of hedge funds is their fee model. The traditional structure is known as “two and twenty”: a 2% annual management fee plus a 20% performance fee on profits. While some funds have shifted to lower management fees or performance fees that apply only to alpha, the reality remains that fees in the hedge fund space are high by any standard.

These fees can significantly reduce net returns, especially in lower-performing years. As institutional investors have become more fee-sensitive, there has been increasing pressure on managers to justify their compensation with performance. Still, even in more modern iterations, hedge fund fees continue to be among the highest in the investment industry.

Hidden Biases in Hedge Fund Performance

When looking at hedge fund returns—especially aggregated through indices—investors should proceed with caution. Unlike equity indexes that include every stock, hedge fund indexes are subject to several biases that can distort the picture.

Selection bias occurs because hedge funds choose whether or not to report their performance to databases. Those with strong returns are more likely to report, skewing the average upward. Survivorship bias further inflates performance by removing the returns of funds that shut down due to poor performance. Backfill bias compounds the issue by allowing new funds to add past performance to the index retroactively, often only if those returns were good.

As a result, the rosy picture painted by hedge fund indexes may not reflect the experience of the average hedge fund investor. Many of the best-performing funds are closed to new capital, while weaker funds quietly exit the scene.

Interested in Learning About Other Hedge Fund Strategies?

Understanding Hedge Fund Risk

Beyond performance, investors must consider the unique risks posed by hedge funds. Liquidity risk is one of the most significant. Many hedge funds have lock-up periods, redemption gates, or infrequent withdrawal windows. This means that capital can be tied up for long stretches, even during times of market stress.

Operational risk is another key concern. Hedge funds are lightly regulated compared to mutual funds and often offer limited transparency into their holdings and processes. This creates the potential for mismanagement—or in rare cases, outright fraud.

Then there’s the impact of fees themselves, which can drag on performance over time, especially if returns fail to reach high-water marks. Even well-intentioned strategies can fall short once the cost of participation is factored in.

Do Hedge Funds Still Diversify?

Despite these concerns, hedge funds can still play a valuable role in portfolio construction. Historical data from 1990 to 2014 shows that hedge funds delivered higher returns than bonds and lower volatility than stocks. In more recent years, however, returns have softened and correlations with equities have increased.

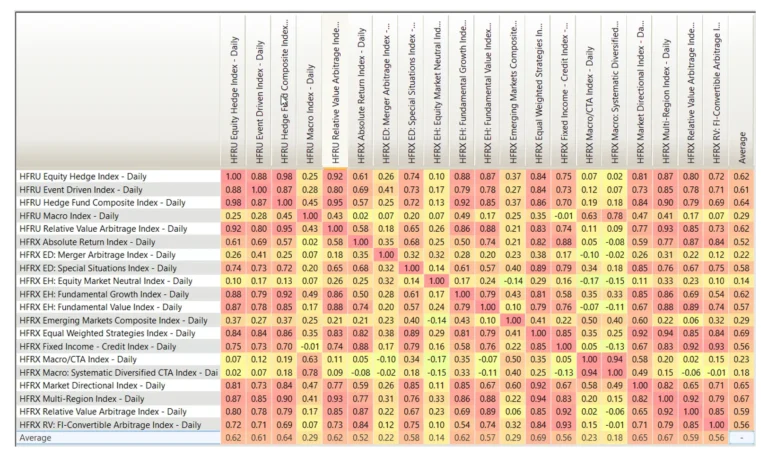

This doesn’t mean hedge funds are obsolete. Rather, their role is shifting. Instead of being a source of outperformance, hedge funds may now be better suited as tools for diversification. Their low or moderate correlation with traditional assets allows them to buffer volatility, smooth returns, and offer exposure to risk factors not present in standard equity or fixed-income portfolios.

The key is selectivity. Not all hedge funds deliver meaningful diversification benefits, and strategy matters. Some approaches are highly market-dependent, while others are genuinely uncorrelated. Investors must dig deep to evaluate which funds justify their place in a portfolio—and which do not.

Final Thoughts

Hedge funds are not miracle machines. They are complex, often opaque investment vehicles that offer the potential for differentiated returns—at a price. Their success depends on manager skill, effective risk management, and strategic alignment with investor goals.

For those with the resources, patience, and due diligence to navigate this world, hedge funds can still serve as valuable complements to traditional investments. But the days of assuming automatic alpha are long gone. In today’s landscape, understanding the true source of returns—and the risks that come with them—is more important than ever.